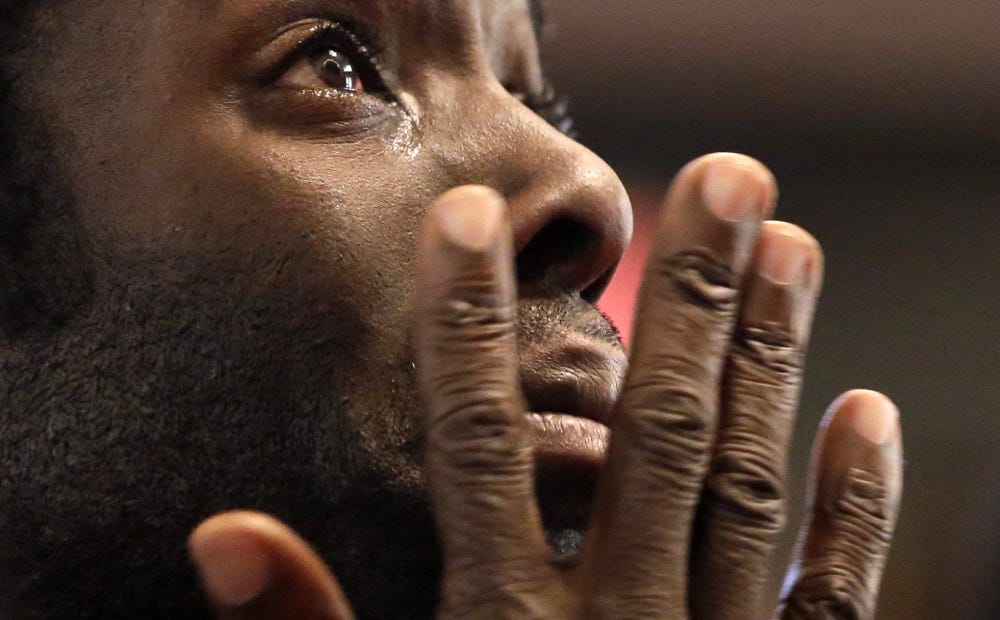

I learned to pray with tears at the lowest point of my ministry.

My church was in turmoil. Consultants and experts in church conflict had no answers. My friends were no help. My soul felt like it was dying on the vine. Worst of all—from the view of a pastor’s ego that prided itself on always having an answer—I couldn’t figure out how to make things right.

A few months earlier, I had done the one thing most experienced pastors would say never do and consolidated our different worship services into a single, blended style. Within a matter of days, my happy congregation became a confused, divided and angry group of people convinced that I had destroyed their church. One of the older guys on my staff warned me in advance what to expect. “It will be like a farmer wrestling with a pig,” he said. “Both get muddy but only the pig likes it.” Personally, I felt more like an elected official who attempts to reform Social Security, forgetting that the popular program is called the “third rail” of American politics because it’s as dangerous as the high-voltage rail that powers a subway—touch it and you die. I touched the third rail in American church life when I changed my congregation’s preferred style of worship. And almost died.

In the weeks following the change, I was convinced each morning when I woke up (if I managed to sleep at all the previous night) that this was the day I’d have to resign. There was too much angst, too much conflict, too many people bailing out to other churches more to their liking for me to continue. I couldn’t make my church members feel better. Couldn’t make the worship work. Couldn’t make people do what I thought they ought to do. As the days dragged into weeks then months, I felt more and more powerless. Don’t get me wrong. The decision hadn’t been made lightly, and I was convinced that unified worship, no matter how long and hard the road was to get there, would be worth it in the end. But the end seemed a long way off and I was desperate enough to start looking around at other options. Should I find another church? Sell insurance? Get a job at Chick-Fil-A?

Trapped between outward storms of failure and inward storms of fear, I took the only action remaining to me. I prayed. Not those professional religious prayers, full of the flowery language, affected intonation and rolling cadences that churches expect from their pastors. Not prayers that parroted what I’d heard from people I thought more spiritual than I was. Instead, I found a deeper, more authentic voice. A voice of grief and desperation. A prayer that acknowledged helplessness and need. I learned to pray with tears.

Maybe you’re in a place like that, where the obstacles you face are greater than the spiritual resources at hand and the normal routines of religion don’t help. Maybe like me in the months following my church crisis, you wonder how to cry out in the darkness and find a God who will not only hear but also help.

Hannah, a biblical character more people need to learn about, can lead you into that kind of prayer.

A National Crisis. A Failed Religion. A Shattered Family. A Broken Heart.

Hannah doesn’t pray in a vacuum. Just as my prayer flowed from a specific moment and set of circumstances, so she prays in a time and place in history. Four pieces of her setting are clear as you read through her story in the first few chapters of the Old Testament book, 1 Samuel.

First, Hannah lives in a time of national crisis. Ever since the Jewish nation had taken possession of the promised land some four hundred years earlier, each of the twelve tribes has essentially governed its own area. Now that arrangement is fraying at the edges. Without a central vision or government, the Jewish people are pulled in a thousand different directions, each tribe or even family pursuing its own agenda. That’s the situation described in the last verse of Judges, the earlier book that sets the stage for 1 Samuel: “In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes.” (Judges 21:15)

Second, like many national crises this one has spiritual roots. The religion of Israel is failing. The vibrant faith that had sustained the Jewish people through their desert wanderings and later led them to conquer the Promised Land has eroded into a shallow, formalistic religion that’s little more than superstition. The sons of the chief priest Eli—they served alongside their father—are poster children for Israel’s spiritual decline. “Now the sons of Eli were worthless men,” we’re told. “They did not know the Lord.” (1 Samuel 2:12)

Third, the national events circling Hannah’s life like storm clouds—as important as they are to what happens next in her story—only provide a framework for understanding why she prays as she does. The opening verses of her story describe something nearer at hand, a threat implied at first but bearing bitter fruit in the following verses

There was a certain man of Ramathaim-zophim of the hill country of Ephraim whose name was Elkanah the son of Jeroham, son of Elihu, son of Tohu, son of Zuph, an Ephrathite. He had two wives. The name of the one was Hannah, and the name of the other, Peninnah. And Peninnah had children, but Hannah had no children. (1 Samuel 1:1-2)

Elkanah, Hannah’s husband, has an impressive lineage and a prominent place in society. He earns a good enough living to support a large household. We learn later that he’s faithful in his religious duties and sees to it that his family worships on a regular basis. He’s attentive and loving toward Hannah. But beneath the skin of this well-positioned, moderately wealthy and apparently religious family, a cancer is eating at the bones. Elkanah has two wives, one with children and the other without, and the rivalry between them is tearing the family apart.

Having multiple wives isn’t unusual with Old Testament figures and Elkanha’s arrangement by itself isn’t the source of his family’s dysfunction. The real problem is that the relationship between Hannah and Peninnah is contentious and destructive. What should be a happy home looks more like one of those TV sitcoms with family members bickering and scheming against each other in humorous ways. Only in Elkanah’s house no one is laughing: “And her rival used to provoke her grievously to irritate her, because the Lord had closed her womb.” (1 Samuel 1:6)

The conflict between Hannah and Peninnah leads to the fourth and final piece of her context. Her prayer flows from a broken heart. In a world that says a woman’s highest purpose is to bear children, Hannah has no value—to herself or to anyone else. Her barrenness is the club Peninniah uses to batter her self-confidence; the label Elkanah uses to make her a victim; the shame she heaps on herself. Worst of all, it won’t end: “So it went on year by year. As often as she went up to the house of the Lord, she used to provoke her. Therefore Hannah wept and would not eat.” (1 Samuel 1:7)

A national crisis, a failed religion, a crumbling family, a broken heart—Hannah prays at the lowest point of her life. But her experience gives hope to anyone who finds themselves in a similar position of crisis.

Tears Take You Places Religion Doesn’t Go

The specific occasion for Hannah’s prayer is one of the annual pilgrimages required by the Jewish religion:

Now this man [Elkanah] used to go up year by year from his city to worship and to sacrifice to the Lord of hosts at Shiloh, where the two sons of Eli, Hophni and Phinehas, were priests of the Lord. (1 Samuel 1:3)

The temple at Shiloh—the main shrine during this period because it housed the ark of the covenant—was a rectangular building consisting of a large room on one side opening into a courtyard on the other. The ark of the covenant was displayed in an alcove along the western wall of the room and served as one of two focal points for worship. The other was the altar located in the center of the courtyard. Made of uncut stones and earth, it was where worshippers gathered to make the prescribed animal sacrifices and celebrate the ritual meals that followed. Benches placed beside the doorway into the main room allowed the priests to keep a watchful eye on worshippers’ behavior.

Elkanah and his fractious family have a predictable and comfortable routine of worship, one that looks much like what we follow today. Arrive at the temple at the appointed time. File past the ark of the covenant—genuflect if you like. Make your appropriate sacrifice at the altar in the courtyard. Follow instructions and sit down to a fellowship meal afterward. Then shake the priest’s hand and tell him what a fine job he did leading the service before packing the kids up and returning home until next time. Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

But this time something is different. While Elkanah and the household gather on one side of the courtyard for the ritual meal, Hannah slips off to the far side of the altar. There, as the happy sounds of her family echo in the distance, she collapses beneath the weight of her failure and grief. Her heart pounds as if it will jump out of her chest. She can’t catch her breath. Her lips form soundless words that fall to the ground along with the tears streaming from her eyes. We’re told that “She was deeply distressed and prayed to the Lord and wept bitterly.” (1 Samuel 1:10)

She’s had enough of ceremony, words and posturing. How can you be at ease at a table filled with laughing people and pretend nothing is wrong? How can you wear a smile when your world is falling apart? How can you pray harmless, little prayers when your heart is breaking? How can you hold back the tears?

Eli, the chief priest, watching Hannah from his perch on one of the courtyard benches, jumps to the wrong conclusion. “How long will you go on being drunk?” he asks. “Put your wine away from you.” (1 Samuel 1:14) Like many religious professionals, he doesn’t understand and even if he did wouldn’t approve of this kind of emotional demonstration during a regular time of worship. Tears are for children who scrape their knees or lose their toys. For women commiserating with other women about petty disappointments. For weddings or funerals as long as they’re shed in a dignified way. Tears should never, though, disturb the order and tranquility of a worship service.

But far more disturbing to Eli— and to many of us—is where Hannah’s tears take her prayer:

And she vowed a vow and said, “O Lord of hosts, if you will indeed look on the affliction of your servant…but will give to your servant a son, then I will give him to the Lord all the days of his life, and no razor shall touch his head.” (1 Samuel 1:11)

Like a mom with a child addicted to drugs, someone waiting by the bedside of a dying friend or an unemployed man frantic to provide for his family, Hannah is distraught enough to make a deal with God. To negotiate a mutually beneficial arrangement. A quid pro quo. “Lord,” she pleads, “if you give me the son I want, I’ll make sure he serves you all his life.” What she has in mind for her son—should her prayer be granted—is for him to become part of the order of the Nazirites, a sect consecrated to God’s service and known for a vow to never cut their hair. (Numbers 6:1-21)

Her prayer offends Eli. I’m sure it wouldn’t do much for many church leaders today, either. I can’t say that it fits into mainstream religion or can be parsed, explained or defended by squeamish theologians. But desperate people do desperate things, and Hannah’s tears lead her into regions of the spirit where deals are made and kept. Maybe God is desperate enough to show mercy that he sometimes bargains, too. Hannah knows a truth we often forget in our well-ordered and comfortable churches. Tears take us places religion doesn’t go.

Your Tears Are Precious to God

I weep more often than I used to because after long believing that showing emotion was a sign of weakness, I’ve come around to believing quite the opposite. There are moments now—a moving scene in a movie, a touching story, certain kinds of music, a worship service—when I cry like a little girl. My wife smiles when she hears me sniffling and sees me wiping my eyes. See there? You’re human after all.

But tears have a larger role to play than just expressing emotion. They can open our heart to God in a way that nothing else does. That’s why the Bible has so much to say about praying and weeping.

For example, Nehemiah—a Jew serving the Persian king Artaxerxes during the exile—prays with tears in the same way and for much the same reason as Hannah. When he learns that his Jewish people back in Jerusalem are living under such dire conditions that their future is in doubt, he’s pushed to the brink. “As soon as I heard these words,” he says in the opening verses of his book, “I sat down and wept and mourned for days, and I continued fasting and praying before the God of heaven.” (Nehemiah 1:4)

Exiled from his homeland, alone and without resources, overwhelmed by the need, Nehemiah does the only thing he can do. He prays…and weeps. And his prayers set in motion the miraculous series of events that brings about the restoration of the Jewish nation.

Another example is Psalm 42. “As a deer pants for flowing streams,” the writer begins, “so pants my soul for you, O God. My soul thirsts for God, for the living God.” (Psalm 42:1) But his search for God then takes the same turn as Hannah’s. While we’re not given the reason or the circumstances, we know that the writer is alone, forsaken and separated from the temple worship that gives his life purpose and joy. That’s what leads him to weep as he prays: “My tears have been my food day and night…These things I remember, as I pour out my soul.” (Psalm 42:3-4) The well-known verse 7, “Deep calls to deep at the sound of your waterfalls; all your breakers and your waves have gone over me,” echoes with the sound of prayer and weeping. Horatio Spafford—mourning the tragic accident that claimed the loss of his four daughters—uses it as the basis for his classic hymn, “It Is Well with My Soul”:

When peace like a river, attendeth my way,

When sorrows like sea billows roll,

Whatever my lot, thou has taught me to say,

It is well, it is well with my soul.

Then there’s the prayer with tears that may be closest to Hannah’s experience—the nameless woman in Luke’s gospel

who was a sinner, [and] when she learned that he [Jesus] was reclining at table in the Pharisee’s house, brought an alabaster flask of ointment, and standing behind him at his feet, weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears and wiped them with the hair of her head and kissed his feet and anointed them with the ointment. (Luke 7:37-38)

Whatever the woman’s background—adultery, theft, prostitution—it has left her in such a state of spiritual need that when she hears of a house party that Jesus is attending, she finds a way into the residence. Slipping through the crowded room, she goes to where Jesus is and, in an act that shocks the respectable religious leaders packed into the room as much as it shocks us today, weeps on the Lord’s feet then wipes them with her tangled, unwashed hair. Everyone knows that she doesn’t belong there. Women like her have no business in a gathering of successful people enjoying good food and interesting conversation. But her desperation drives her to brave the ridicule sure to follow her act and find the only One who will listen to her broken heart.

The woman’s act of weeping at the feet of Jesus is prayer by another name. A prayer more authentic than any phrased in religious jargon the Pharisees who judged her could utter. And it’s answered in the same way as was Hannah’s many centuries before. As your prayers can be answered, too. Jesus leans close and whispers so that only she can hear, “Your faith has saved you; go in peace.” (Luke 7:50)

Our tears are precious to God. That’s the secret learned by the company of people through the ages—Hannah, Nehemiah, the Psalmist, the woman who wept on Jesus’s feet and many others—who risked praying without restraint or caution. “That’s why You record my lamentations; put my tears in your bottle. Are not these things noted in your book?” (Psalm 56:8 in The Book of Common Prayer)

The Gift of Tears

Hannah’s weeping as she prays for a child isn’t an interesting detail of the larger story—color commentary with details like her family dynamics or tidbits about religious practices of the time. It’s the main point; at least, from the human perspective.

More than the expression of desperation, grief or failure, Hannah’s tears are a gift that release her from what Maggie Ross in her book The Fountain and the Furnace: The Way of Tears and Fire calls the prison of her own ego and position her to receive God’s answer:

It cannot be emphasized enough that the gift of tears is a gift. Like any other gift, it can be accepted or rejected. While it cannot be forced or manipulated it can, like unceasing prayer of which it is a part, be nurtured. It is an “ambient” grace. It is not the special possession of a spiritual elite but always available, waiting to find us receptive. It is an ineffable gift, and one of its distinguishing marks is that it always points us away from our selves even as it illuminates our selves.

I know about Hannah’s gift of tears because that’s what led to the resolution of the crisis that began this essay. Things in my church didn’t end the way I expected them to. I wasn’t forced to resign. The congregation and I didn’t negotiate a compromise style of worship. There wasn’t one of those church splits that Baptists are famous for, with one group leaving to start a new church more to their liking. I didn’t die. But over the next year or so things started to change. The congregation began to find a fresh voice in worship. People who liked the new worship moved in to replace those who left because they didn’t. Old staff left the church while new staff more in tune with the new direction came on board. I was able to sleep again. Like Hannah, I learned that

Those who sow in tears shall reap with shouts of joy! He who goes out weeping, bearing the seed for sowing, shall come home with shouts of joy, bringing his sheaves with him. (Psalm 126:5-6)

Praying with tears opens doors that won’t open any other way. Maybe if your prayers have grown stale and frustrating and you wonder if there’s any use in praying at all, you should look to Hannah. Maybe you should learn to pray with tears.

I get it… and I’ve been there. Staying takes more courage unless The Lord is clear on the direction. Glad you stuck with it and while some do not like leadership decisions… then they might not be in leadership. It is not for the faint of heart as leadership is often about making decisions people do not agree with but it is for the good. In the long run. We don’t make all the right decisions but we can make all decisions right.

I appreciate your ability to communicate the challenges in your life. Not many can.

Here come those tears again…